SPOTLIGHT

|

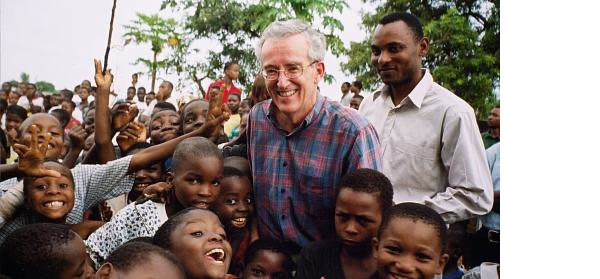

Peter Bell: An Unreconstructed Idealist

Years later Princeton University honored him with its Madison Medal, the university’s highest honor for a graduate alumnus, describing him as “a humanitarian and leader in the struggle to give hope and voice to the most vulnerable in this nation and throughout the world.”

Together these honors framed his life and work and provide an apt description of what he himself said was more a “calling” than a career, a lifetime of helping others whose lessons he shared with a Princeton audience in 2005, not long before he retired.

“Hang on to your idealism,” he said, “let it be the source of your inspiration and energy. After 40 years of public service, I remain an unreconstructed idealist, wiser perhaps but not the least jaded by my decades of experience….What makes my blood run faster about public service are the opportunities to resolve conflict, to make peace, to bring about justice, to protect the vulnerable, and to support the poor and disadvantaged.”

Peter Bell died April 4 at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston after a long struggle with cancer, surrounded by his family. He was 73.

He lived in nearby Gloucester, an old fishing town where he was born and grew up, having moved back there with his wife, Karen, in 2007, a year after he retired as president of CARE.

It was in that ocean-side town, while in high school, that his interest in international affairs, nurtured by a family involved in the community, blossomed into a commitment.

Crucial to this development was a trip he took to Japan on an American Field Service scholarship as a member of the first group of high school students to visit that country after World War II. He was impressed by his host family’s desire to seek reconciliation with the United States. His host mother’s maxim, “make the world more wonderful”, and his relationship with the Okajimas, he often said, strengthened his faith in the “oneness of humanity”. A diary of his experiences was published as the book Junket to Japan, one of his many writings.

His youthful education in international affairs developed further when, as an undergraduate at Yale University, he traveled to the Ivory Coast in the summer of 1960 with a racially integrated group under the auspices of Operation Crossroads Africa to build a school.

And it was at Yale that he was inspired by a command to his students from a philosophy professor, Paul Weiss, the first Jewish full professor at the university: “Go forth and make the world less miserable.”

But retirement to Gloucester did not mean he stopped caring and continuing to work on humanitarian issues. He wrote and spoke about the need to reduce poverty worldwide, and for increased human rights and peacemaking efforts, and backed up his vision through voluntary work with a vast and varied group of organizations.

Most notably, he became a Senior Research Fellow at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University and, recently, had been chair of the NGO Leaders Forum, which brought together the heads of America’s largest humanitarian non-governmental organizations to explore major issues of national and international concern.

He began his career with Ford after receiving a master’s degree at the Woodrow Wilson School of International Affairs at Princeton. He stayed with the Foundation for 12 years, all but two of them as its representative in Brazil and then Chile. Those were eventful years in both countries and Peter was at the center of efforts to preserve and protect human rights under military dictatorships.

In Chile, where he became head of the Foundation’s office, he was declared a “suspicious person” by the government and warned by the United States government that he should leave the country. He stayed, however, and with the Foundation’s support helped save the lives and careers of hundreds of Chilean scientists and scholars, many of whom at some point had been detained and tortured.

“….his first love and strongest connection was with Latin America,” writes Abraham Lowenthal in the Spring issue of the Latin American Studies Association’s LASAFORUM, “especially with the disadvantaged, the victims of human rights abuses, and the courageous social scientists and civil society activists striving to build democratic governance.

“In his years with the Ford Foundation, Peter took farsighted decisions, opposed at the time by local governments, U.S. government officials, and powerful private interests, but importantly supported by Foundation president McGeorge Bundy,” writes Lowenthal, who worked for Ford with Bell in Latin America.

Peter Hakim, who also worked with Peter Bell in Latin America, says that in Chile in 1971 “Peter moved quickly to reshape the Foundation’s program so it reached beyond one political party. He built a grant portfolio that reflected Chile’s political and ideological diversity. In the process, he secured the credibility and access the Foundation subsequently needed to respond to the military repression following Salvadore Allende’s overthrow in 1973.

“What the Foundation did was to assist a great number of academics and policy analysts pursue their careers outside Chile, where they feared their lives were in danger. It aided an even greater number continue their work in the country, often in institutions it helped create. Nothing the Foundation did in Chile—perhaps in Latin America—received more attention or is more remembered.”

Further testament to his imprint in the region came from Ana Toni, Ford’s representative in Brazil from 2003 to 2011 and now head of a consulting firm in Rio. “Peter Bell left a huge legacy to the Brazilian office,” she wrote. “The essential and very difficult role that the Foundation played during the Brazilian dictatorship, especially for being an American foundation, created the conditions for Ford’s important work during the democratization process.”

Raymond C. Offenheiser, president of Oxfam America and a Foundation official in Peru from 1986 to 1996, praised Peter’s personal and professional skills. “In an era when the art of statesmanship is rare,” he wrote in a tribute published in The Chronicle of Philanthropy, “Peter Bell carried himself in a way that allowed him to build relationships with unwavering integrity. He could eat breakfast with peasants, lunch with presidents, and dinner with human-rights activists.

“He moved fluidly across boundaries with humility and grace, seeking little recognition while achieving tremendous impact by imparting wisdom gleaned from each of these unique worlds….

“While ever the gentleman, he brought gravitas, courage, charm, and a passionate sense of conviction to a life devoted to human rights and social justice. As an activist in a pinstriped suit, he gave respectability to the vocation.”

After leaving Ford, Peter became a special assistant and then Deputy Under Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare during the administration of President Jimmy Carter. He then began work with a series of private organizations, all devoted to humanitarian and human rights causes.

He was president of the Inter-American Foundation, supporting grassroots development in Latin America; Senior Associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, working toward the return to democracy in Chile and settlement of the civil war in El Salvador; president of the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, improving conditions for people who are poor and disadvantaged in the United States, and president of CARE, one of the largest relief and development organizations in the world.

He headed CARE from 1995 until he retired in 2006. The current president of the organization, Helene D. Gayle, noted at his death that Peter was “an unwavering champion for the rights of the poor, for social justice and had an important role in shaping CARE into the organization it is today.”

Raymond Offenheiser wrote that “….Peter pushed all of us to see poverty as social exclusion and to fight the policies and barriers that limit the poor from securing the resources and opportunities they need to pull themselves out of poverty. Peter had come to see poverty as less about scarcity and more about lack of power. The solution lay in enabling the powerless to use their voices and make reasonable demands for the realization of their rights.” (Offenheiser’s full article appeared in the April 16 issue of The Chronicle and is on its website at philanthropy.com)

In addition to writing and speaking engagements, he was involved through volunteer efforts as co-chair of the Inter-American Dialogue, chair of the Bernard Van Leer Foundation, chair of CARE USA, a director of Human Rights Watch, a director of the International Center for Research on Women, a trustee of the World Peace Foundation, a member of the advisory board of the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard, a member of the Steering Committee for the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, and a trustee of Rockport Music, an organization devoted to excellence in classical music and jazz.

In a message, the family painted a picture of his private side. “Peter reveled in visiting his two granddaughters in London,” they said, “having monthly breakfasts with his large, extended family in Gloucester, walking with Karen and their dog, Sophie, in all weather along the granite-bound Black Shore, playing tennis, attending special exhibits and lectures at the Cape Ann Museum, enjoying performances in the concert hall at Rockport Music, picnicking in the glow of the sunset at Halibut Point State Park, going to services and concerts at the Unitarian Universalist Church, and hosting family members and friends from near and far.”

In addition to his wife, Peter is survived by his son, Jonathan Neva Bell, and his wife, Veronique, of London, England; his daughter, Emily Dexter Bell, and her fiancee, David Tyree, of New York City; his granddaughters, Melanie and Jessica; his brothers, John and his wife, Janis, of Gloucester, David “J.J.” and his wife, Jacquelyn, of Gloucester, and Timothy of Gloucester; a sister, Diana Bell of Palo Alto, Calif., and a brother-in-law, Cleveland Cook of Gloucester.

|