NEWSLETTER

|

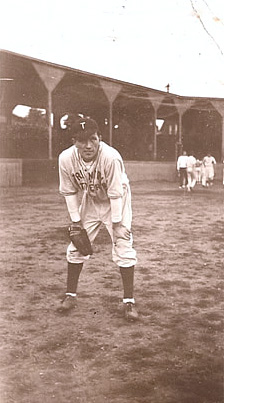

Frank Sutton, former international vice president, whose passing at age 95 was reported in the last newsletter, had been writing his memoirs when he died. His son Pip has shared with us a 30-page, single-spaced document he had been working on, a reminiscence of his ball playing days in and around Newtown, Pa. A fluid writer and a constant presence at the computer, Sutton describes in detail growing up in small-town America. His recollections are of sufficient general interest to warrant excerpting. We pick up the narrative near the end of the document, his account of playing with the Trenton (New Jersey) Potteries. With respect to baseball, Sutton admits he was good enough to play semi-professionally, but he opted to go to Temple University to study mathematics, to Princeton for a graduate degree, and then to Harvard as a junior fellow for a Ph.D. in sociology.

It’s rather unfortunate that I have to trust to distant memories to tell something of my baseball experience after the beginning of the 1937 season (Sutton had kept a diary and newspaper box scores while in high school.) We did go on to some exciting games in the new league. I particularly remember games in Trenton against the O’Donnells, the toughest team and our great rivals. They had some good players, including an infielder named Case who went on to the Big Time and who was especially notable for stealing bases.

Somehow, we lured Holsclaw back on the mound and became serious competitors to the O’Donnells. The most dramatic game with them that I remember was played in Newtown, with Holsclaw pitching for us. He was doing very well, striking out many batters. One of the O’Donnell team was a short, tough fellow I later came to know quite well at the Trenton Potteries but remember only as “little Mike”. He was a noisy fellow that day, complaining that Holsclaw’s pitches were “sailing.” Sometime along in the game, he was at bat and suddenly ran out to the pitcher’s mound and tore off Holsclaw’s glove. He triumphantly found in it a piece of sandpaper that Holsclaw had been using to rough up the cover of the ball. I don’t remember that we were penalized in any way for this dirty play. My recollections are that Holsclaw showed no remorse at being caught. I do remember his saying, “If I thought he was going to come all the way out to the mound, I would have hidden the sandpaper.”

In the summer of 1937 (after my diary dies), I began a new baseball life with the Trenton Potteries. I was really quite a decent ballplayer and could hit the ball in all the leagues I played in. I played first base for the Potteries team and was a reliable hitter against all the pitching in that league. The right field fence was rather far out, and I didn’t often knock one over it, but sometimes I did. As I recall those years, Robbie Robinson and Sam Wiggins began with other teams in the league, but I have box scores in which they are on our team, as the lead-off and # 2 batters. Indeed, I have a clipping of a game when we beat the C.V. Hill team and nudged them out of first place in the League. Robbie, Sam, and I all had home runs that night, and the newspaper reports that “Old Reliable” Flop Ferry came on in relief to save the game for us.

There were doubtless less happy nights, but we Newtown youngsters were very happy to have jobs and games to play on a decent field in a well contested league. I suppose there were some who resented these young ballplayers taking jobs from older fellows with families and badly in need of work. But I never remember being chased out of a Trenton bar. My recollection is that I continued to play and work in Trenton in the summer of 1938 before I went that fall as a graduate student at Princeton.

After working in the summer of 1936 at Cold Spring Bleachery in my father’s Finishing Department, I was glad in the summers of 1937 and 1938 to get a job at the pottery in Trenton. 1937 was of course the ill-famed year when Washington tried prematurely to cut back on Depression-era stimuli and move toward balancing the federal budget. The result was the 1937 plunge back into depression, with loss of the gains in employment that had been achieved in earlier years. It was a hard time to find a job and I was only able to get one because they wanted me to play on the ball team. I earned a basic salary of $18 a week, which didn’t seem bad to me—there were men around me trying to support themselves and their families on that amount. They put me to work on a drill press under the eye of a supervisor who wanted to see that I worked, and with others around me who wanted to be sure I wasn’t doing too much of it and threatening their jobs. These people wanted me to hustle on the ball field, not in the plant.

I have good memories of those evenings on a ball field somewhere on the south side of Trenton. We were a good enough team to be serious contenders in the Industrial League and we were much supported by officers and staff of the potteries.

(Sutton ends his report on the baseball years with a section titled “Aftermath—L’Envoi,” as follows:)

What became of all this? A very few years later, indeed from about 1938 when I went to Princeton, I ceased to play organized ball myself, and I was starting to neglect the box scores and the standings. When I first went to Temple in 1934, there were those who thought I might try to play college ball there, but I never tried to do so. It simply wasn’t a feasible thing for a commuting student, living about 25 miles from the city...And I must confess that I did not think I was cutting off a promising career in baseball. I had gone to Temple on a couple of scholarships, neither of them for my athletic prowess. There had been scouts around our ball teams and a couple of our players in the Industrial League went on up the ladder to the Big Time. But I was never importuned and don’t think I deserved to be. I was an unusually good hitter for a fellow my size. I remember my old friend, Jurgen Kroger, telling me one night when I came back to watch my successors at Pickering Field, “None of these kids can hit it out there as far as you used to do.” I felt good about that but I knew that if I was to make my way out of Newtown to the wide world, it had to be on abilities other than ones for the ball field. I had signs of such other abilities.

Still, I’m happy to report that there are some in Newtown who thought I have wasted my talents. When I used to trudge up Chancellor Avenue to Pickering Field in my uniform and spikes, I regularly passed the Waugh residence on that street. There was a son in that heavily female household named Charles C. Waugh. He went to George School, on to Princeton, and then to a respectable career building and marketing flowmeters in California. In his retirement he wrote and published his memoirs, Friends Indeed/A Bucks County Family History. I have this book through the kindness of Esther Pownall who lived at the end of the lane where my father first taught me to throw and catch a ball, and who was much befriended by my sister after the rest of her family died away. At p. 102, Waugh writes:

“A local youth, Francis X. Sutton, was an outstanding high school ball player and student as well. He elected to go to Harvard, to the dismay of Spider Burns, the local baseball guru. ‘What a waste of talent’, he complained. Sutton later achieved a distinguished career in the Harvard faculty.”

I hear talk these days that the kids don’t play baseball like they used to, particularly as one goes farther West. Maybe the urbanization of the population is to blame; maybe television and computers, too. Maybe the Hispanic kids make a hopeful counter trend, trying to imitate the Rodriguezes and Fernandezes and Ramirizes who are taking over the Big Leagues. If indeed all this is true, I naturally deplore any decline of baseball for the kids even while deploring the high prices and commercialization of the Big Time. While the “nature deprivation” that comes with urbanization and indoor electronics is perhaps even more troublesome, one must mourn if kids don’t learn to hit a fast ball or catch a hot liner. Perhaps even more, one must regret the loss of experience of playing hard but fairly to win in a team sport. It was a sexist time when I grew up, and playing ball was part of the strong distinction between boys and girls. Things are properly different now, and I don’t prescribe what is best to do about adapting baseball to these new times. I do like to think that the boys of my generation learned things that were right and good but within rules and an unwritten ethic. Even if we come to a post-sexist time, I hope the boys, and even the girls, will still learn to field a hot grounder, leap high for a drive over their heads, get air in their lungs, and some tan on their faces!

|