NEWSLETTER

|

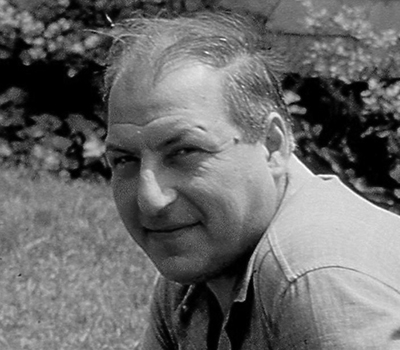

Kalman Silvert in the Ford Foundation

By Peter S. Cleaves and Richard W. Dye

From 1966 to 1976, Kalman Silvert was Senior Social Science Advisor to the Ford Foundation’s Office for Latin America and the Caribbean (OLAC). He had established himself as a leading United States intellectual on Latin American politics and as a prolific writer on the region, and during his life had been a professor at Tulane University, Dartmouth College and New York University.

He was also a founder of LASA, the Latin American Studies Association. LASA’s first congress, in June 1966, was attended by about a dozen academics. Fifty years later, LASA had 7,802 members (43 percent from Latin America), of whom 6,419 attended its fiftieth anniversary congress in New York City.

To commemorate the anniversary, Abraham Lowenthal and Martin Weinstein have edited a volume devoted to Kal’s career, Kalman Silvert: Engaging Latin America, Building Democracy, issued earlier this year by Lynne Rienner Publishers and written with Ford Foundation support. Persons with firsthand knowledge of Kal’s life wrote chapters on his contributions to development theory, teaching and mentoring, research methodology, hemispheric relations, and democratic values. There are 13 contributors, including the former president of Chile, Ricardo Lagos. The chapter we wrote covers Kal’s important role in the Ford Foundation during a conflictive decade for Latin America.

The chapter draws on a large body of Ford Foundation memoranda and reports deposited at the Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC) in Sleepy Hollow, N.Y. We also conducted interviews with Kal’s associates in the Foundation, former grantees and colleagues. Foundation staff who shared their memories are Peter Bell, William Carmichael, Norman Collins, Robert Edwards, Richard Fagen, Shepard Forman, Barry Gaberman, Peter Hakim, Lowell Hardin, James Himes, Abraham Lowenthal, Jeffrey Puryear, Paul Strasburg, James Trowbridge and Evelyn Walsh. Colleagues and grantees quoted in the chapter include Sergio Bitar, José Joaquín Brunner, Julio Cotler, Alejandro Foxley, Manuel Antonio Garretón, Elizabeth Jelín, Ricardo Lagos and Riordan Roett. (Sadly, between our interview and the book’s publication, Peter Bell and Lowell Hardin passed away.) For their historical value, we plan to place the transcribed interviews in the Ford Foundation archives at RAC.

Kal had considerable influence on the Foundation’s mission to strengthen academic excellence in Latin America and the Foundation’s response to the assault on academic freedom during the period of brutal military governments in South America. His role with other committed Foundation colleagues was fundamental in rescuing academics whose careers and even lives were threatened. Kal embodied an operating style that influenced Foundation policy even though he did not command budgetary resources or line authority. We argue that his legacy and attributes, as well as the findings in other chapters of the Lowenthal / Weinstein volume, hold lessons for today’s professionals in support of academic and international advancement.

In 1966, the social science disciplines were rudimentary in most Latin American universities. Formalistic academic writings offered little of value for designing public policies that addressed poverty, discrimination, economic growth or democratic participation. Silvert considered that building local competence in sociology, economics and anthropology would in turn generate knowledge that well-intentioned governments could utilize for designing practical approaches to their country’s development challenges.

The guiding principles were an emphasis on academic quality, democracy and freedom of expression. The practical applications were providing advanced graduate training for promising young Latin Americans in the social sciences at world centers of excellence, and greatly strengthening academic departments in Latin America’s major universities.

After Silvert’s arrival, the Ford Foundation greatly expanded its support for the social sciences at Latin American universities through graduate fellowships and research funds for hundreds of scholars and financing for scores of universities, notably in Chile, Argentina, Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, Peru and Central America. Silvert reported to the OLAC heads, Harry Wilhelm and Bill Carmichael, who agreed with a direction that differed from the Foundation’s work in Asia and Africa, which relied heavily on foreign consultants to advise governments on development policy.

The results of discipline- and institution- building have been fundamental and longstanding. Latin American social science today is world-class with robust university departments and high productivity. Senior Latin Americans attribute much of this progress to the Foundation’s (and Kal’s) early contributions. Of note: 2,748 of the 6,419 attendees at the May 2016 LASA meeting were affiliated with Latin American universities.

During Silvert’s tenure, the military overthrew civilian governments in Bolivia, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Bolivia and Peru, and became harsher in Brazil. The Chilean, Argentine and Brazilian regimes were particularly repressive and targeted social scientists as enemies of the state, confronting the Foundation with decisions on how to respond to humanitarian, program and political issues.

The Foundation, led in Chile by the Santiago office and in New York by OLAC, including Silvert, assisted LASA and others to develop a range of employment and study scholarships in the United States, Canada, Europe and Latin America to provide opportunities for those affected. The strategy also included negotiating with the authorities on releasing prisoners so they could accept positions abroad. More than fifteen hundred scholars, intellectuals and political refugees were able to relocate, one of whom, Ricardo Lagos, was destined to become President of Chile and a contributor to the Silvert legacy volume.

The Foundation’s response to program issues occurred in two phases. First, the Foundation, as was its long tradition, did what it could to support and sustain grantees negatively affected by the coups. In a few cases, it was possible to do this, at least for a while, within the context of the universities or other institutional arrangements, but more often grantees were forced or chose to leave to try to develop opportunities in the private sector. In due course, the bulk of the Foundation’s original program was closed down, the most significant case being the termination of the multi-million dollar ten-year program of collaboration between the University of Chile and the University of California.

The second program phase was undertaken after heated debate within the Foundation over the merits and demerits of remaining active in these near-totalitarian countries. The Foundation ultimately decided to maintain its presence in Santiago and Buenos Aires in order to execute a radically different program, at least so long as it was permitted to do so by the governments.

This program, which Silvert played a major role in designing, had three components. The first was to help create and support new civil society institutions separate from the military-led universities, founded in some cases by previous Foundation grantees. The second was research grants that provided institutional support, funded analyses and kept a cadre of social scientists engaged in their specialty. The third was a large graduate fellowship program to train a new generation of scholars from throughout the Southern Cone. The three programs were predicated on the Foundation’s hypothesis that the military would eventually return to the barracks and the countries would transition to democracy. The hypothesis subsequently proved correct.

The final set of issues, the political one, revolved around the fact that by taking an active role in assisting refugees from the military regimes and persuading a number of countries to join in doing so, by openly cutting and trimming its programs in response to the coups, and by mounting a new and sustained effort to assist civil society in the two countries to lay the groundwork for future democratic development, the Foundation de facto became a significant political actor. Silvert, who had more to do with the conceptualization and execution of the Southern Cone program than anyone else, clearly was comfortable with the Foundation’s activism. It is to the Foundation’s credit that there was also broad institutional support for it.

In our chapter, we strove to identify what seemed to lie behind Silvert’s influence in the Foundation, despite his lack of formal levels of authority. They include Kal’s deeply held values, intellectual integrity, theory of social change, disciplined focus on programmatic outcomes, sympathetic, respectful, engaging personality, success in recruiting like-minded allies, skill in “managing upward” and extreme hard work.

Kal tragically did not live long enough to see the ultimate success of the Southern Cone strategy and the programs he had so much to do with creating. On June 15, 1976, at the age of 55, Kal died of a heart attack.

Peter S. Cleaves was with the Ford Foundation’s Latin America and Caribbean office from 1972 to 1982, including as Representative for Mexico and Central America. He later held executive positions at First Chicago, University of Texas, AVINA Foundation and Emirates Foundation (Abu Dhabi). Richard W. Dye worked in the International Division from 1961 to 1981, the last seven years as Representative for the Southern Cone, before joining the Institute of International Education (IIE) as Executive Vice President.

______________________

The other articles that deal with Latin America:

By Jeffrey Puryear

By Rebecca Reichmann Tavares

|