NEWSLETTER

|

The Rise and Fall of “The City at 42nd Street” By George Gelles

Of the Ford Foundation’s myriad initiatives undertaken through the years, few promised such close-to-home benefits as The City at 42nd Street, an effort I joined in 1977.

In memory, it’s all but forgotten. In fact, a sanitized and family friendly entertainment hub along 42nd Street between 7th and 8th Avenues superseded its vision. Grand aspirations, however, characterized the project’s genesis, and this very grandiosity perhaps presaged its failure.

A major metropolis harbors major sins, and New York provided a panoply of questionable diversions at least as early as the 1830s, the heyday of Five Points in lower Manhattan. On his first U.S. sojourn, during which he spent a month in Manhattan, Charles Dickens wrote of that area, “All that is loathsome, dropping and decayed is here.”

Forty-Second Street’s glittering apex, and that of surrounding Times Square, was reached around the turn of the 20th century, when theaters and hotels of unrivaled opulence set an elegant tone. With Prohibition, however, the area’s complexion began to change, live drama replaced by increasingly tawdry films, and the haut monde giving way to honky-tonk. The street’s entertainments were said to be “no runs, no hits, just terrors”. It was a “hotbed for getting hot and heavy,” according to The New York Daily News (which at the time of this assessment was itself headquartered on 42nd Street), with rampant drug use and various sorts of sex for sale.

Despite decades of intermittent interest in the block’s improvement, progress seemed impossible. By the mid-1970s, however, a critical consensus had coalesced that urged dramatic change. The New York Times regularly offered dire descriptions of 42nd Street between 7th and 8th Avenues: it and its neighborhood were “tawdry, blighted and sometimes frightening”, it must be “save(d) from sin and decay”, “it’s Kung Fu and sex from one end of the street to the other.”

Seeds of The City at 42nd Street were planted by members of the Urban Design Group, which, as related by the Harvard Graduate School of Design, was “(f)ounded in 1967 as part of New York City Mayor John Lindsay’s office (and whose members) championed the theory and practice of enmeshing design with politics and law.

“Architects Jaquelin Robertson, Jonathan Barnett and Richard Weinstein, co-founders of the UDG, along with lawyer Donald Elliott, then chair of the New York City Planning Commission, used incentive zoning, special districts and transfer of development rights, among other legal techniques, to implement their vision of a vibrant, walkable city.”

Two of the group became principals in the Ford Foundation’s efforts, which were underwritten by a $500,000 grant: Donald Elliott (who, while at Yale Law School, had written a paper that favorably discussed the ideas set forth in Jane Jacobs’ seminal study of The Death and Life of Great American Cities) and Richard Weinstein, who at the time was Director of Mayor Lindsay’s Office for Planning and Development for Lower Manhattan. Weinstein is credited with having first imagined the contours of The City at 42nd Street.

Joining them in the project’s leadership was Martin Stone, a broadcasting executive and entertainment lawyer, whose most germane credential was his tenure as head of the Industrial Division of the 1964 World’s Fair, in Flushing Meadows, Queens. With “Power Broker” Robert Moses, the Fair’s director, he won the participation of dozens of blue-chip American corporations, whose pavilions were paeans to their achievements.

The triumvirate reported to Roger Kennedy, who, after a prominent if somewhat peripatetic career—he was a government attorney, a journalist, a banker—had joined the Foundation in 1969 as Vice President for Finance.

After spending six years writing for The Washington Star and most recently having served as director of a week-long conclave in Philadelphia that explored commonalities between science and the arts, I was invited to join the project in 1977, working most specifically as Stone’s assistant and more generally as the initiative’s factotum.

Early in my tenure, Kennedy and Stone asked me to represent the Foundation in a search for suitable office space. Meetings ensued with representatives of the former Pan Am Building (now the MetLife Building), which sits atop Grand Central Terminal and demarcates Park Avenue north and south, and, on the Foundation’s behalf, I secured, gratis, a former Pan Am ticket office, 5,000 square feet facing Vanderbilt Avenue.

Then, after meeting with Guy Tozzoli, head of the World Trade Department of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey—he was the force behind the development of the former World Trade Center—I was given my choice, gratis as well, of office furnishings for our endeavors, furnishings of a luxe rarely seen by nonprofits.

Although knowing that groundwork for my success was laid by relationships first cultivated by others, by Roger himself and by Martin, Roger generously named me the project’s Administrative Director. Though my responsibilities didn’t appreciably change, I now sat closer to the proverbial table and was able to observe more closely The City’s evolution.

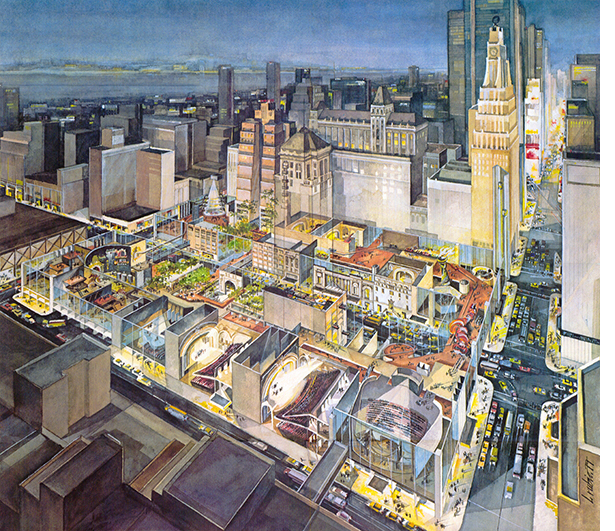

Paul Goldberger, then architecture critic for The New York Times, described the initial plan: It would “take over the entire block (of 42nd Street between 7th and 8th Avenues), condemn it as a city urban-renewal project, and then erect an elaborate structure that would contain theaters, studios, exhibitions and multi-media displays, all intended to provide an introduction to the city and its cultural life.”

Despite having “the cautious approval of the Koch administration” (Edward Koch, in 1978, became New York’s 105th Mayor, succeeding Abraham Beame, who had replaced Mayor Lindsay in 1974), Mayor Koch smelled a whiff of the theme park.

“New York,” he proclaimed, “cannot and should not compete with Disneyland—that’s for Florida. People do not come to Manhattan to take a ride on some machine. This is a nice plan and we want to be supportive—but we have to be sure that it is fleshed out in a way appropriate to New York. We’ve got to make sure they have seltzer instead of orange juice.”

That’s “cautious approval”, indeed.

In response, perhaps, to Koch’s critique, The City refined its vision, stressing educational aspects as well as entertainment. The model was Epcot, the most high-minded sector of the Walt Disney World Resort, then still being developed. From its opening in 1982, Epcot—Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow—was in its own words “dedicated to the celebration of human achievement, namely, technological innovation and international culture, and is often thought of as a ‘permanent world’s fair’.”

What Martin Stone so successfully achieved at the 1964 World’s Fair, he perhaps again could accomplish on 42nd Street.

After substantive meetings with some of New York’s finest—Hugh Hardy, an architect with a special genius for historic renovation, especially for theaters, and Ivan Chermayeff, graphic artist and exhibit-design consultant nonpareil—a model was made that showed The City in miniature. Then, Robert Moses, master builder of the New York metropolitan area, was invited to the Foundation to view the maquette.

Greeted by Martin Stone, his former colleague, and introduced to the principals and Foundation personnel, Moses studied the model, which sat atop a conference table. After an appropriate interval, his first comment was a question: “Where’s the parking?”

Had anyone anticipated the need for parking? Was there a plausible answer or was one improvised on the spot? For a man who deeply believed in building roads—highways, expressways, freeways, parkways, causeways —that dramatically increased vehicular traffic, thus necessitating the building of more roads still, it was a telling remark. Today, approximately 40 years after Moses’ query, Manhattan, perhaps more than ever, still grapples with traffic.

The City changed further. On or near the block, at one time or another, there were discussions of a Portman hotel, a Helmsley merchandise mart, an office tower built by the Canadian firm of Olympia & York and a 15-story high, indoor Ferris Wheel. Some plans advanced, others were discarded, and the process excited interest from other major developers, who sought to join Olympia & York, Portman and Helmsley as possible participants.

Among those showing interest were Cadillac Fairview, Brandt, Rockrose and Frederick DeMatteis and Charles Shaw, developers of the Museum Tower, above MOMA on 53rd Street.

Optimism was tempered with doubt, as is evident in a statement made by the head of the Citizens Housing and Planning Council. Awash in the conditional, it raises equivocation to an art: “Originally it was all fantasy, but it is starting to look real at some levels. People are beginning to take the plans somewhat seriously and there is a perception that maybe something can happen if the city is willing to commit itself to large-scale renewal.”

The city wasn’t willing to commit, at least not to the plan proposed by The City at 42nd Street. Soon after his inauguration, Mayor Koch withdrew municipal support. Shortly thereafter, he announced a plan of his own, whose outlines were unmistakably similar to the work done under Ford Foundation auspices.

From my vantage point, it was Realpolitik unalloyed. The new mayor, a Democrat and self-described “liberal with sanity”, would not, could not endorse a plan, however well-conceived, that was developed by leading members of a former Republican mayoral administration, liberal though it was.

Dissecting the situation in The New York Times Magazine, reporter Ralph Blumenthal wrote that The City at 42nd Street plan “incensed Mayor Koch, then newly elected, who considered it monopolistic—one nonprofit concern headed by two former city planners was predesignated as the sole developer. On the Mayor’s orders, the proposal was scrapped ….”

Phillip Lopate—critic, poet and passionate New Yorker—gets the last words: Of Times Square, he writes that “All of Manhattan tilts toward that magnetic field of neon. Have you ever tried ambling through the streets of New York without any destination? I know that I am always pulled… at first into the triangle around Times Square, with the three-card-monte sharks and the Bible screamers and the sad-eyed camera stores; I am bobbed around in that whirlpool until I turn up on the street, West 42nd, between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. Then I don’t know where to start to turn my head around and look….”

Like Jane Jacobs, city-lover of a different stripe, he advocates energy, density and diversity of all sorts—economic, ethnic and artistic, with cultural fare catering to every brow, high, middle and low. Whether these values will be preserved by the current iteration of 42nd Street, another observer must report.

I remained associated with the Foundation after The City’s demise, until 1981 working with W. McNeil Lowry—to everyone, Mac—in the Office of the Arts (which became the Office of Education and Public Policy when Franklin Thomas succeeded McGeorge Bundy as Foundation president).

With Mac, I helped write and edit the position papers that were discussed at the 53rd American Assembly, held at Arden House and directed by Mac, whose topic was “The Future of the Performing Arts”. And joining his superb program officers in theater, dance and music, Ruth Mayles, Marcia Thompson and Dick Sheldon, respectively, I worked, in consultation with both Dick and Mac, with organizational applicants in music.

Mac and his colleagues, program officers of broad knowledge and deep sympathies, helped make my tenure at the Foundation singularly privileged.

|