NEWSLETTER

|

Agent Orange: Looking Forward By Charles Bailey

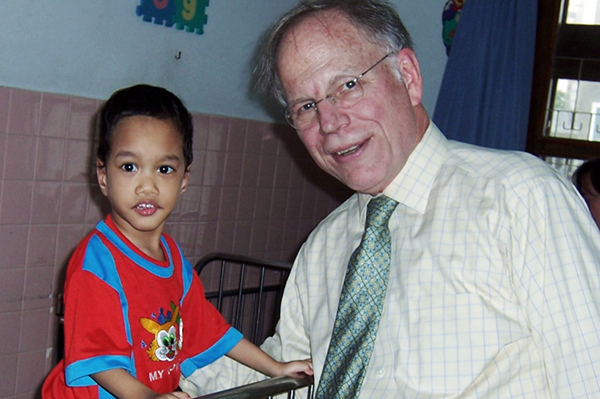

For the next 22 years he was the Foundation’s representative in Dhaka for 5 years, Nairobi for 7 and Hanoi for 10. He then moved to New York to direct Ford’s Special Initiative on Agent Orange/Dioxin. “I was fortunate to have such opportunities,” he says. ”Being the Ford Foundation representative is absolutely the best job in the world!”

Now, he says, he continues to use the Aspen website “to show how it is possible to now bypass the fierce politics of the past on Agent Orange and to update about 30,000 visitors on the unfolding progress between the two governments.”

This article is adapted from a speech he made in January in Hanoi at the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam.

The Diplomatic Academy was practically my first stop when I arrived in Hanoi in 1997 and it is a real pleasure to return. To answer Prof. [Fred] Brown [of the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University], the Ford Foundation invested about $20 million through 110 grants in international relations in Vietnam over a 15-year period. The grants funded the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Academy and related agencies to send their staff for overseas study, conduct research and organize conferences.

But among those conferences I want to particularly highlight the Academy’s conference on “The Future of Relations between Vietnam and the United States” in October 2003, which Director-General Trinh Quang Thanh and Professor Brown organized in Washington, D.C. The honest and often warm ambiance of the conference demonstrated beyond doubt that both Vietnamese and Americans—official and unofficial—were determined to broaden and deepen the bilateral relationship.

It was this mix of official and unofficial participants, and the skillful guidance of Ambassador Trinh Quang Thanh and Professor Brown, that permitted informal, friendly and frank discussion.

We started with the easy part—the briskly growing trade between the two countries—, went on to the somewhat more challenging—China and regional security—and ended up in the most challenging: the legacies of the war and especially Agent Orange.

At the time Agent Orange was still an extremely sensitive subject. The Vietnamese authorities and the U.S. government were literally poles apart on the impacts on the environment and on human health. But as Bui The Giang, one of the participants in the conference, put it, “Like it or not, we have to talk about [Agent Orange] and deal with it, and recognize the fact that all cases come from people who lived in areas, or were related to people, affected by Agent Orange. This is an issue that must have a humanitarian solution.”

The Conference Report concluded that “Without waiting for any formal resolution, the U.S. Government should be more sensitive to the Vietnamese views on the Agent Orange issue.”

The conference thus helped set the stage for a turning point on Agent Orange: a joint statement by President George Bush and President Nguyen Minh Triet in November 2006. The statement acknowledged the benefits to be had from U.S. help with cleaning up the dioxin at former military storage sites in Vietnam. The statement created new possibilities, but did not provide the practical and tangible means to move ahead.

There the matter might have remained but for two initiatives, one from a member of the U.S. Senate Appropriations Committee, Sen. Patrick Leahy, and his staff member, Tim Rieser, and the other from the president of the Ford Foundation, Susan Berresford, and myself.

In December 2006 I approached Vice Minister Ambassador Le Van Bang, who invited us to continue the work we had begun in 2000 on Agent Orange. So we continued. We filled in the missing middle ground between the two poles with other actors: local NGOS, international NGOs, 17 American foundations, UNDP, UNICEF and the governments of Ireland, the Netherlands, Greece and the Czech Republic.

Between 2000 and 2011, the Ford Foundation invested $17.1 million in 82 grants for work on Agent Orange.

How were these funds used?

In Vietnam, Ford grant recipients developed treatments and support services for Agent Orange victims; identified and began to clean up dioxin hotspots; and rebuilt rural livelihoods in areas that had been sprayed. These actions benefited more than 10,000 Vietnamese in eight provinces.

In the U.S., Ford grantees engaged with policy makers in Washington and reached out to the American public, who were unaware that dioxin continues to be a significant problem for Vietnam. The American public and lawmakers now agree that “Agent Orange is a humanitarian concern we can do something about.”

And we helped launch a Track II process. In February 2007, one of your senior colleagues, Madame Ton Nu Thi Ninh, Susan Berresford and Walter Isaacson, the president of the Aspen Institute, launched an eminent persons group. It’s called the U.S.-Vietnam Dialogue Group on Agent Orange/Dioxin and is the first two-way, genuinely free-flowing, channel between the U.S. and Vietnam on Agent Orange. In 2010 the Dialogue Group released a Plan of Action that laid out what is needed to bring this legacy to an end.

Let me return now to Senator Leahy’s leadership on this issue. Since 2007 the U.S. Congress has appropriated a total of $136 million for Agent Orange in Vietnam. This breaks down to $105 million for clean-up of dioxin-contaminated soils at the Da Nang and Bien Hoa airbases and $31 million for health/disability services.

This Congressional funding, implemented by USAID, has already had a positive impact on the bilateral relationship. For example, after the ground-breaking in August 2012 for the clean-up of the Da Nang airport, a Vietnamese friend said to me: “With every decade that passed with no action, our hopes dwindled that anything would ever be done about Agent Orange. Now we see the U.S. government taking action. We think it helps turn us to a new page in our relationship.”

This is progress worth celebrating. The environmental clean-up promotes further progress on what is the heart of the matter: a full response, to the extent possible, to the needs of people with disabilities linked to dioxin exposure, that is, to the Agent Orange victims. Senator Leahy and his Congressional colleagues have just presented us a way to do this.

The Senator visited Da Nang last April (2014) for the “power up” of the giant $84 million furnace that is now busily destroying the dioxin on the airbase. In his speech he said: “Today we are here to pay tribute to the joint United States–Vietnamese effort to address the legacy of Agent Orange… [Our goal is] to show that, after so many years, the United States did not ignore this problem. We returned and we are taking care of it…[Another goal is] to improve services for people with disabilities, regardless of the cause, including [those] which may have been caused by Agent Orange.”

You will notice the two uses of “cause” in that sentence. The first, “regardless of cause,” represents the U.S. State Department’s position, which does not recognize a link between dioxin exposure and ill health and birth defects. The second usage in the same sentence is “services for people with disabilities….including [those] which may have been caused by Agent Orange.”

That was April 2014. In December the U.S. Congress approved the 2015 Appropriations Act and President Obama signed it into law. The Act contains two key passages on health/disability services and Agent Orange.

First: “…funds appropriated under the heading ‘Development Assistance’ shall be made available for health/disability activities in areas sprayed with Agent Orange or otherwise contaminated with dioxin.”

And second: “[These funds] should prioritize assistance for individuals with severe upper or lower body mobility impairment and/or cognitive or developmental disabilities.”

The Act thus makes it clear that the funds for health/disability services will need to be more tightly focused. Specifically, future American assistance for health/disability services should focus first and foremost on the people with severe physical and/or mental disabilities who live in areas that were sprayed with Agent Orange or in areas near dioxin hotspots.

People in our two countries and indeed people all over the world now know that Agent Orange is a humanitarian concern we can do something about. This Act helps us to better get on with that task. Now we need a new discussion between the governments of the U.S. and Vietnam and deft diplomacy on both sides.

U.S. government assistance to victims of unexploded ordinance has for many years helped everyone with a traumatic injury, whether or not it came from an unexploded bomb or some other cause. Assistance to people with severe disabilities would work the same way.

For the Vietnamese, the first concern is providing services to Agent Orange victims. Research I conducted in Da Nang a year ago shows that a very large majority of Agent Orange victims are people with the conditions named in the Act. Funds will always be limited in relation to the needs, but this focus ensures that the majority of the available American funding will help people of greatest concern.

|